|

| |

Sons of Confederate Veterans,

Camp #16

Confederate Flag History

| |

|

The Bonnie

Blue

The Bonnie Blue Flag, a single white star on a blue field,

was the flag of the short-lived Republic of West Florida. It

was created by Melissa Johnson, sister-in-law of Major Isaac

Johnson, commander of the West Florida Dragoons. In September

1810, settlers in the Spanish territory of West Florida revolted

against the Spanish government and proclaimed an independent

republic. The Bonnie Blue Flag was raised at the Spanish fort

in Baton Rouge on September 23, 1810. On December 6, 1810,

West Florida was annexed by the United States and the republic

ceased to exist, after a life of 74 days.

When Mississippi seceded from the Union on January

9, 1861, as a sign of independence, the

Bonnie Blue Flag was raised over the capitol building

in Jackson. On January

26, 1861,

In addition to the national flags, a wide variety of flags

and banners were flown by Southerners during the War. Most

famously, the "Bonnie Blue Flag" was used as an

unofficial flag during the early months of 1861. It was flying

above the Confederate batteries that first opened fire on

Fort Sumter. |

| |

|

|

The

First National, The Stars and Bars

March 5, 1861 - May 1, 1863

The first

official flag of the Confederacy, called the "Stars and Bars," was

flown from March 5, 1861, to May 26, 1863.

The very first national flag of the Confederacy

was designed by Prussian artist Nicola Marschall in Marion,

Alabama. The Stars and Bars flag was adopted March

4, 1861 in Montgomery, Alabama

and raised over the dome of that first Confederate Capitol.

Marschall also designed the Confederate uniform.

One of the

first acts of the Provisional Confederate Congress was

to create the Committee on the Flag and Seal, chaired by

William Porcher Miles of South Carolina. The committee

asked the public to submit thoughts and ideas on the topic

and was, as historian John M. Coski puts it, "overwhelmed

by requests not to abandon the 'old flag' of the United States." Miles

had already designed a flag that would later become the Confederate

battle flag, and he favored his flag over the "Stars

and Bars" proposal. But given the popular support for

a flag similar to the U.S. flag ("the Stars and Stripes"),

the Stars and Bars design was approved by the committee.

When war broke out, the Stars and Bars caused confusion on

the battlefield because of its similarity to the U.S. flag

of the U.S. Army.

Eventually, a total of thirteen stars would

be shown on the flag, reflecting the Confederacy's claims

to have admitted Kentucky and Missouri into their union.

The first public appearance of the 13-star flag was outside

the Ben Johnson House in Bardstown, Kentucky. The 13-star

design was also used as the basis of a naval ensign. |

| |

|

|

The Second

National - March 1,1863

During the solicitation

for the second national flag, there were many different

types of designs that were proposed, nearly all making

use of the battle flag, which by 1863 had become well-known

and popular. The new design was specified by the Confederate

Congress to be a white field "with

the union (now used as the battle flag) to be a square of

two-thirds the width of the flag, having the ground red;

thereupon a broad saltier [sic] of blue, bordered with white,

and emblazoned with mullets or five-pointed stars, corresponding

in number to that of the Confederate States."

The nickname "stainless" referred

to the pure white field. The flag act of 1864 did not state

what the white symbolized and advocates offered various

interpretations. The most common interpretation is that

the white field symbolized the purity of the Cause. The

Confederate Congress debated whether the white field should

have a blue stripe and whether it should be bordered in

red. William Miles delivered a speech for the simple white

design that was eventually approved. He argued that the

battle flag must be used, but for a national flag it was

necessary to emblazon it, but as simply as possible, with

a plain white field.

The flags actually made by the Richmond Clothing

Depot used the 1.5:1 ratio adopted for the Confederate Navy's

battle ensign, rather than the official 2:1 ratio.

Initial reaction to the second national

flag was favorable, but over time it became criticized

for being "too white".

The Columbia Daily South Carolinian observed that

it was essentially a battle flag upon a flag of truce and

might send a mixed message. Military officers voiced complaints

about the flag being too white, for various reasons, including

the danger of being mistaken as a flag

of truce, especially on naval ships, and that it was

too easily soiled. This

flag is nonetheless a historical symbol of the civil war. |

| |

|

|

Third

National Flag ("the Blood Stained Banner")

(Since 4 Mar 1865)

The third national flag was adopted March 4, 1865, just

before the fall of the Confederacy. The red vertical stripe

was proposed by Major Arthur L. Rogers, who argued that the

pure white field of the second national flag could be mistaken

as a flag of truce. When hanging limp in no wind, the flag's Southern

Cross canton could accidentally stay hidden, so the

flag could mistakenly appear all white.

Rogers lobbied successfully to have this

alteraton introduced in the Confederate Senate. He defended

his redesign as having "as

little as possible of the Yankee blue", and described

it as symbolizing the primary origins of the people of the

South, with the cross of Britain and the red bar from the

flag of France.

The Flag Act of 1865 describes the flag

in the following language: "The Congress of the Confederate

States of America do enact, That the flag of the Confederate

States shall be as follows: The width two-thirds of its

length, with the union (now used as the battle flag) to

be in width three-fifths of the width of the flag, and

so proportioned as to leave the length of the field on

the side of the union twice the width of the field below

it; to have the ground red and a broad blue saltire thereon,

bordered with white and emblazoned with five pointed stars,

corresponding in number to that of the Confederate States;

the field to be white, except the outer half from the union

to be a red bar extending the width of the flag." |

| |

|

|

The Battle Flag

Often referred to as "The" battle flag of the

Confederacy it was the design that was the basis of more

than 180 separate Confederate military battle flags.

The Army

of Northern Virginia battle flag was usually square,

of various sizes for the different branches of the service:

48 inches square for the infantry, 36 inches for the artillery,

and 30 inches for the cavalry. It was used in battle beginning

in December 1861 until the fall of the Confederacy. The

blue color on the saltire in the battle flag was navy blue,

as opposed to the much lighter blue of the Naval Jack.

The flag's stars represented the number of states in the

Confederacy. The distance between the stars decreased as

the number of states increased, reaching thirteen when the

secessionist factions of Missouri and Kentucky joined

in late 1861.

At the First

Battle of Manassas, the similarity between the Stars

and Bars and the Stars and Stripes caused confusion and

military problems. Regiments carried flags to help commanders

observe and assess battles in the warfare of the era. At

a distance, the two national flags were hard to tell apart.

In addition, Confederate regiments carried many other flags,

which added to the possibility of confusion. After the

battle, General P.G.T.

Beauregard wrote that he was "resolved then to

have [our flag] changed if possible, or to adopt for my

command a 'Battle flag', which would be Entirely different

from any State or Federal flag."He

turned to his aide, who happened to be William Porcher

Miles, the former chair of Committee on the Flag and Seal.

Miles described his rejected national flag design to Beauregard.

Miles also told the Committee on the Flag and Seal about

the general's complaints and request for the national flag

to be changed. The committee rejected this idea by a four

to one vote, after which Beauregard proposed the idea of

having two flags. He described the idea in a letter to

his commander General Joseph

E. Johnston: "I wrote to [Miles] that we should

have two flags — a peace or parade flag,

and a war flag to be used only on the field of

battle — but congress having adjourned no action will be

taken on the matter — How would it do us to address the

War Dept. on the subject of Regimental or badge flags made

of red with two blue bars crossing each other diagonally

on which shall be introduced the stars, ... We would then

on the field of battle know our friends from our Enemies."

The flag that Miles had favored when

he was chair of the Committee on the Flag and Seal

eventually became the battle flag and, ultimately,

the most popular flag of the Confederacy. According

to historian John Coski, Miles' design was inspired

by one of the many "secessionist

flags" flown

at the South Carolina secession convention of December,

1860. That flag was a blue St

George's Cross (an upright or Latin cross) on a red field,

with 15 white stars on the cross, representing the slave

states, and, on the red field, palmetto and crescent

symbols. Miles received a variety of feedback on this design,

including a critique from Charles Moise, a self-described "Southerner

of Jewish persuasion". Moise liked the design, but asked

that "the symbol of a particular religion not be made

the symbol of the nation." Taking this into account,

Miles changed his flag, removing the palmetto and crescent,

and substituting a heraldic saltire ("X") for the

upright one. The number of stars was changed several times

as well. He described these changes and his reasons for making

them in early 1861. The diagonal cross was preferable, he

wrote, because "it avoided the religious objection about

the cross (from the Jews and many Protestant sects), because

it did not stand out so conspicuously as if the cross had

been placed upright thus." He also argued that the diagonal

cross was "more Heraldric [sic] than Ecclesiastical,

it being the 'saltire' of Heraldry, and significant

of strength and progress."

Although Miles described his flag as a heraldic saltire,

it had been thought to be erroneously described since the

latter part of the 19th century as a cross, specifically

a Saint

Andrew's Cross. Supposedly this folk legend sprang from

the memoirs of an aging Confederate officer published in

1893. However, further research has indicated that this was

no folk legend. In 1863, during the session in which the

Confederate Congress was voting on the 2nd National Flag,

William G. Swan of Tennessee's second congressional district

wished to substitute the following language:

"That the flag of the Confederate States shall be

as follows:

A red field with a Saint Andrew's cross of blue edged with

white and emblazoned with stars."

|

| |

|

|

The Confederate Battle Flag

What is now often called "The Confederate

Flag" or "The Confederate Battle Flag" (actually

a combination of the battle flag's colors with the second

naval jack design), despite its never having historically

represented the CSA as a nation, has become a widely recognized

symbol of the

South. It is also called the "rebel", "Southern

Cross, or "Dixie" flag,

and is often incorrectly referred to as the "Stars and

Bars" (the actual "Stars and Bars" is the

First National Flag, which used an entirely different design).

During the first half of the 20th century the

Confederate flag enjoyed renewed popularity. During World

War II some U.S. military units with Southern nicknames,

or made up largely of Southerners, made the flag their unofficial

emblem. The USS

Columbia (CL-56) flew a Confederate Navy Ensign as a

battle flag throughout combat in the South Pacific in World

War II. This was done in honor of the ship's namesake, the

capital city of South Carolina, the first state to secede

from the Union. Some soldiers carried Confederate flags into

battle. After the Battle

of Okinawa a Confederate flag was raised over Shuri

Castle by a Marine from the self-styled "Rebel Company" (Company

A of the 1st

Battalion, 5th Marines). It was visible for miles and

was taken down after three days on the orders of General

Simon B. Buckner, Jr. (son of Confederate General Simon

Buckner), who stated that it was inappropriate as "Americans

from all over are involved in this battle". It was replaced

with the flag of the United States. |

| |

|

All rights reserved AlabamaDepartment

of Archives & History

|

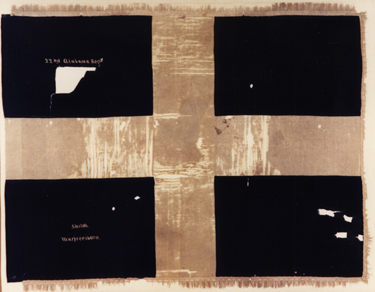

The Original 5oth Alabama

Infantry Battle Flag

Provenance Reconstruction:

Organized in March 1862, this regiment was originally designated

as the 26th Alabama Infantry. This designation was later

changed to the 50th Alabama Infantry. The date that this

flag was issued is unknown, however, its use will post date

December 1863 when Joseph E. Johnston assumed command of

the Army of Tennessee. Johnston had new battle flags of this

pattern issued in the early spring, 1864.

Following the war, former Lt. Colonel

Newton Nash Clements apparently retained possession of

the flag. Dr. Thomas Owen, Director, Alabama Department

of Archives and History, began writing Mrs. N. N. Clements

concerning the flag on October 22, 1904. Over the years,

he continued to request the donation of the flag which

was finally forwarded to the Department on August 7, 1909.

The flag was donated by Mrs. Clements and her daughter

Miss Belle Cements. The accession log entry of August 12,

1909 describes the flag as "badly mutilated". |

| |

|

22ND ALABAMA INFANTRY REGIMENT - ALABAMA

DEPARTMENT OF ARCHIVES AND HISTORY , MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA.

|

22ND ALABAMA INFANTRY REGIMENT - ALABAMA |

| |

|

|

|

|